The Global Forum for Combating Anti-Semitism, which met last week in Jerusalem, needs focus.

Activists gathered last week in Jerusalem for the “Global Forum for Combating Anti-Semitism,” under official Israeli government auspices.

This is not something to be taken for granted. Not always has the State of Israel seen the struggle against anti-Semitism as its fight. For the first 25 years of Israel’s existence, the unspoken attitude in Jerusalem seemed to be “if Jews abroad have a problem with anti-Semites they can always migrate to Israel.” Immersed in the business of building and defending the Jewish nation-state, Israel’s leaders had no time for “troubles of the Diaspora past.”

Attitudes began to change after the Yom Kippur war. The campaign of political delegitimization against Israel launched by Arab countries led to the infamous “Zionism is Racism” resolution at the UN and a ton of propaganda that blended anti-Zionism with anti-Semitism. The Big Lie entered intellectual discourse.

After the Rue Copernic synagogue bombing in Paris in 1980 and other terror attacks, Prime Minister Menachem Begin took the decision to have Israeli officials begin advising Jewish communities abroad on security measures, and the response to anti-Semitism rapidly found its place on the national agenda.

With the disintegration of the Communist bloc, an enhanced role for Israeli diplomacy regarding anti-Semitism also became more necessary and possible. Jerusalem intervened and pressed for government crackdowns on official and street manifestations of anti-Semitism in the emerging states of the former USSR.

The wave of neo-Nazi violence that swept Germany in 1993 generated a demand for Israeli government action against anti-Semitism. The Knesset held its first-ever special debate on the matter, and one former Mossad chief suggested publicly that Israeli agents act against neo-Nazi leaders.

Anti-Semitism emanating from the Arab world became an issue as well. When President Hosni Mubarak visited Washington in 1997, congressmen roughly confronted him with the issue of anti-Semitism in the Egyptian press.

In 1988, then-Cabinet Secretary (and later Supreme Court Justice) Elyakim Rubinstein established an “Inter-Ministerial Forum for Monitoring Anti-Semitism,” and expanded it to include Diaspora Jewish representatives and academic experts.

The Forum and the Anti-Defamation League founded the Tel Aviv University Project on Anti-Semitism in 1992, a documentation and research center. The Project compiled reports on anti-Semitism around the world and eventually won a place on the Israeli cabinet’s agenda, reporting once a year.

Subsequently, the World Jewish Congress joined the consortium, and began to convene an annual conclave of researchers and activists who monitored anti-Semitism around the world.

In 1997, Cabinet Secretary Danny Naveh assumed responsibility for combating anti-Semitism, and he wanted to push for global legislation that would limit access to sources of hate literature, such as neo-Nazi web sites on the Internet. But for years, this never happened. At the time, many American Jewish groups opposed this approach because it suggested limits on free speech.

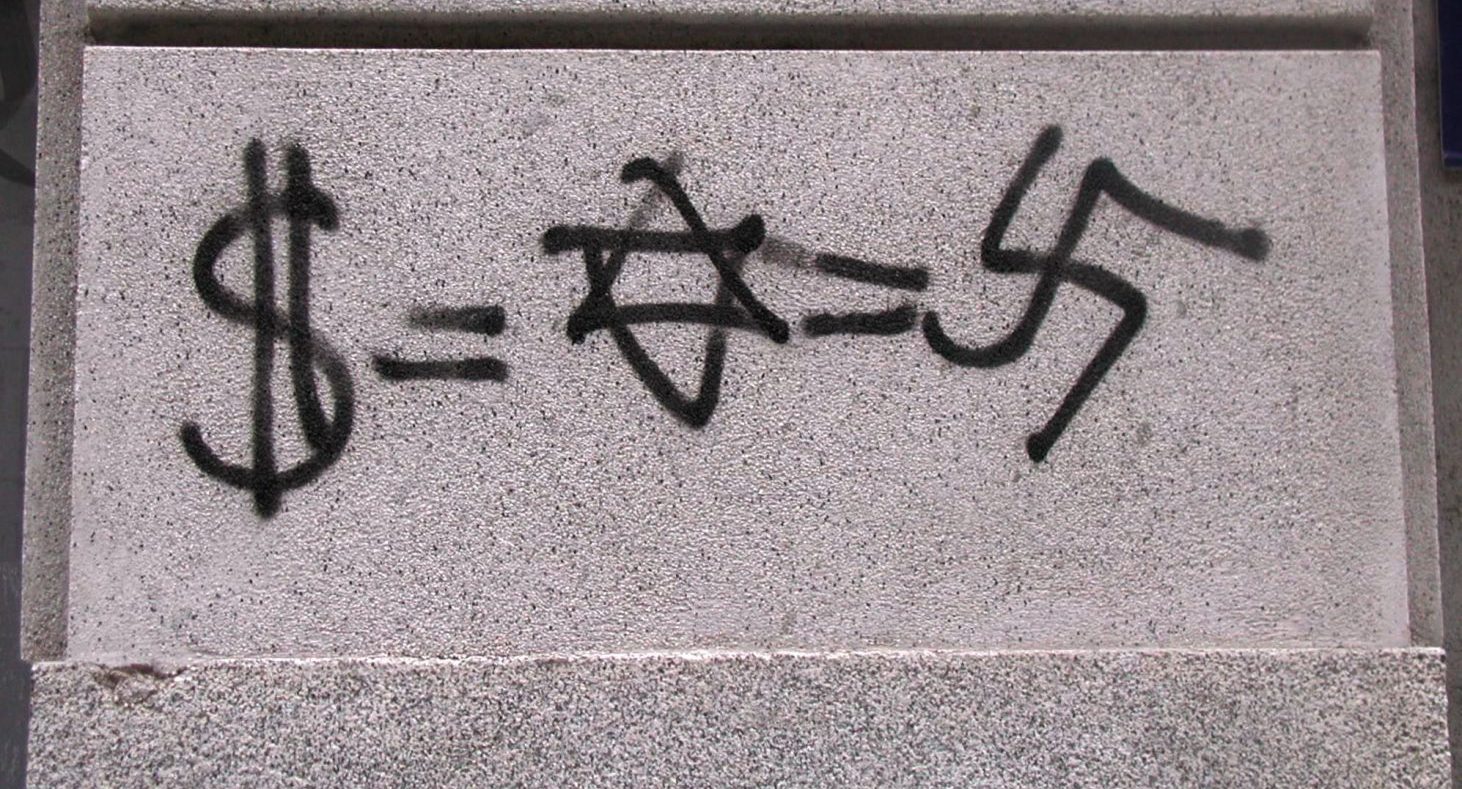

In retrospect, this was a terrible mistake, considering the monstrous proportions to which anti-Semitism on social networks and the web has grown. Belatedly, everybody now agrees that combating “cyberhate” is a top priority, and Israel’s Justice Ministry even has a department dedicated to the fight against online incitement.

The 2001 World Conference against Racism, known as Durban I, turned into one of the greatest displays of organized anti-Jewish and anti-Israel hate ever. It was horrible watershed moment that clarified how anti-Semitism had become a strategic threat. It traumatized even many Israelis.

Shortly thereafter, Natan Sharansky became Minister for Jerusalem and Diaspora Affairs, and in 2003 he founded the Global Forum against Anti-Semitism. Sharansky’s leadership and heroic global reputation made the Global Forum into a focused and super-effective coordinating body of Jewish leaders, intellectuals and organizations.

“The State of Israel has decided to take the gloves off and implement a coordinated counteroffensive against anti-Semitism,” Sharansky wrote. “The State of Israel will play, as it always should, a central role in defending the Jewish People…”

Natan Sharansky’s contribution was enormous – and for this reason, and many others, he richly deserves to be an Israel Prize laureate, as was announced this week. Natan focused attention on “new anti-Semitism,” which aims to emasculate the Jewish People by whittling away at the Jewish State.

Sharansky developed simple benchmarks to distinguish legitimate criticism of Israel from anti-Semitism. His “3D test” scrutinized criticism of Israel for demonization, double standards and delegitimization – which mark the devolution of commentary about Israel into the dark zone of anti-Semitic expression and intent.

In 2010, Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper formally adopted Sharansky’s 3D definition as his own, in a compelling speech delivered at a meeting in Ottawa of the Inter-Parliamentary Coalition for Combating Anti-Semitism.

Then in 2016, the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) adopted a similar working definition of anti-Semitism, which includes using double standards to single out Israel, or denying the Jewish people their right to self-determination. (By this definition, it is anti-Semitic to claim that the existence of a State of Israel is a racist endeavor, to compare Israel to Nazi Germany, or to use symbols associated with classic anti-Semitism like the blood libel to characterize Israel or Israelis).

But as Prof. Gerald Steinberg has shown, much of the self-styled human rights community has studiously ignored the IHRA framework. Groups such as Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and the World Council of Churches reject the definitions described above, and frequently stray into anti-Semitic territory in their incessant and fierce criticism of Israel.

At the second and third Global Forum meetings, Sharansky focused attention on radical Islamist and Arab anti-Semitism, and on Palestinian anti-Semitism. He wasn’t prepared to gloss over this, especially since satanic imagery about Jews and Israel became commonplace in the Palestinian media and was directly leading to violence.

Again, today everybody acknowledges what Sharansky understood back then: That one of the main reasons for the collapse of the Oslo peace process was our failure from day one to confront lies and diabolical indoctrination in the Palestinian Authority; an authority that Israel helped establish in order to concede territory and find peace, but instead became an anti-Semitic and anti-Israel monster.

SINCE THEN, THE GLOBAL FORUM has met in Jerusalem many times. Under the auspices of the Israeli foreign and diaspora ministries it has morphed from a modest professional coordinating forum of core Jewish activists into a large and lavish international conference with cultural performances, expensive dinners, and swag.

This year’s conference was open to almost any member of the public. This meant that many disgruntled or otherwise bored hangers-on, who didn’t belong at a serious policy conference aimed at tangible results, were around to rant and harangue. This wasted a lot of time. It left me hankering for the good old days of Natan’s unassuming and more genuine forum where small working-groups brainstormed and crafted actual plans to combat anti-Semitism.

To their credit, the conveners of this year’s Global Forum smartly used the gathering as a platform for the participation of many non-Jews (even some Moslem leaders), and as a platform where foreign government leaders could publicly commit themselves to fighting anti-Semitism and defending Israel.

But my sense was that the conference conveners couldn’t decide on what to focus this year, so they turned the conference into a profligate potpourri of anti-Semitic problems.

Just about every anti-Semitic ill you can imagine was on the agenda: Hate of the Left and hate of the Right, cyberhate, LGBTQ hate, Christian theological anti-Semitism, Holocaust revisionism, Palestinian denialism of Jewish history, campus anti-Semitism, legislative assaults on Jewish practices like ritual slaughter and circumcision, and even anti-Semitism in sports.

In a world where anti-Semitism has reached post-Holocaust epidemic proportions, there are indeed a lot of bases to cover.

However, Israeli tax dollars might have been better spent, and the real fight against global anti-Semitism better served, had the Global Forum been more focused around a single or several key issues.

The Forum could have usefully devoted its entire agenda to combating “intersectionality” as a cover for hate speech in progressive activism, or to countering the anti-Semitism of far-right political parties in Europe (some of whom have taken to masking their hate by proclaiming to be also pro-Israel).

There were short and excellent presentations on these two topics, respectively, by Sohab Ahmari and David Bernstein; and by Natan Sharansky and Ariel Muzicant.

But in the crush and rush of some 100 speakers and 1,200 participants packed into mammoth plenary sessions over two days, and with all that food to consume, there wasn’t enough time to delve into either topic seriously or to craft concrete strategies of response.

Published in The Jerusalem Post and Israel Hayom, March 23, 2018.

JISS Policy Papers are published through the generosity of the Greg Rosshandler Family.

photo: By Yonderboy (Own work) [GFDL , CC-BY-SA-3.0 or CC BY 2.5 ], via Wikimedia Commons

- בניית אתרים

- בניית אתרים